FOREWORD: The Tanner Family Legacy at 2908 W. Diamond Street, Philadelphia, PA.

Authored by Dr. Rae Alexander-Minter, July 2024. We present her essay here in full, which recovers various family histories and provides a platform for continued inquiry, informing further conversation and possibly newly commissioned research. We thank our beloved elder for the breadth of her offering to us.

Dear Colleagues, Friends of The Tanner House, and Devotees of North Philadelphia’s Sustainability,

Your successful endeavor in securing the structure of the landmarked family home of Henry Ossawa Tanner, the renowned 19th-century artist slated for demolition, was a victory, a transformative source of inspiration and pride for all who value our shared history.

ON THE TANNER FAMILY LEGACY:

The Tanner House, situated at 2908 W. Diamond Street, was acquired in 1872 by my great grandfather, Bishop Benjamin Tucker Tanner, a stalwart of the Tanner family. His purchase was not just a transaction but the beginning of a legacy that inspires us today.

Rev. Tanner's influence extended beyond the walls of the Tanner House. He founded the AME Review, a quarterly magazine that became a leading journal on the literary erudition of African Americans. His role as the editor of The Christian Recorder, a church newspaper that published information about national politics and church news, further solidified his impact.

In 1888, Rev. Benjamin Tucker Tanner was consecrated as Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). He was the author of seven books on ecclesiastical topics and a strong advocate for racial solidarity and educational equity. His dedication to these causes and his ability to speak and read Hebrew inspired many. My mother (Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander) often told me that Rabbis and the Jewish lay ministry would visit Bishop Tanner at his Diamond Street home and engage in lengthy discussions on religious and racial issues.

The formidable historian Dr. Carter G. Woodson described Bishop Tanner’s home as “the center of the African American intellectual community of Philadelphia and the Northeast United States.”

In 1893, Bishop and Mrs. Tanner’s son, the artist Henry Ossawa Tanner, returned home from Paris, France, where he lived and studied art after leaving Philadelphia, PA., in 1891. For one year, 2908 Diamond Street became his studio. Henry Ossawa Tanner completed his iconic painting, The Banjo Lesson (1893), in this legendary home.

The Banjo Lesson demonstrates the unsentimental affection and tenderness between an elderly African American man and a Black youth whom he teaches to play the banjo. The banjo is a significant musical instrument in American history and folklore; it is not a prop for Tanner. It is a symbol, a metaphor, for passing on traditions, one’s heritage, and education from one generation to another.

Bishop Tanner’s granddaughter and my mother, Sadie Tanner Mossell, lived in this residence as she pursued her graduate studies in Economics at the University of Pennsylvania.

In 1921, Sadie Tanner Mossell was awarded the Ph.D. degree in Economics by the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Mossell was the first African American, regardless of gender, to receive a Ph.D. in Economics in the United States. However, she was denied a career in economics because she was Black and a woman.

Sadie Tanner Mossell was the first national president of the venerable organization Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., which held business meetings in the Tanner House at 2908 W. Diamond Street. As I research and study my mother’s history, I have learned to appreciate her dedication to the mission and the members of this sorority throughout her life. Sadie Tanner Mossell experienced severe racial isolation as a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania. Delta Sigma Theta served as her North Star; she cherished her friendships and found comfort in the stimulating, welcoming environment. My mother maintained these friendships with her sorors throughout her life.

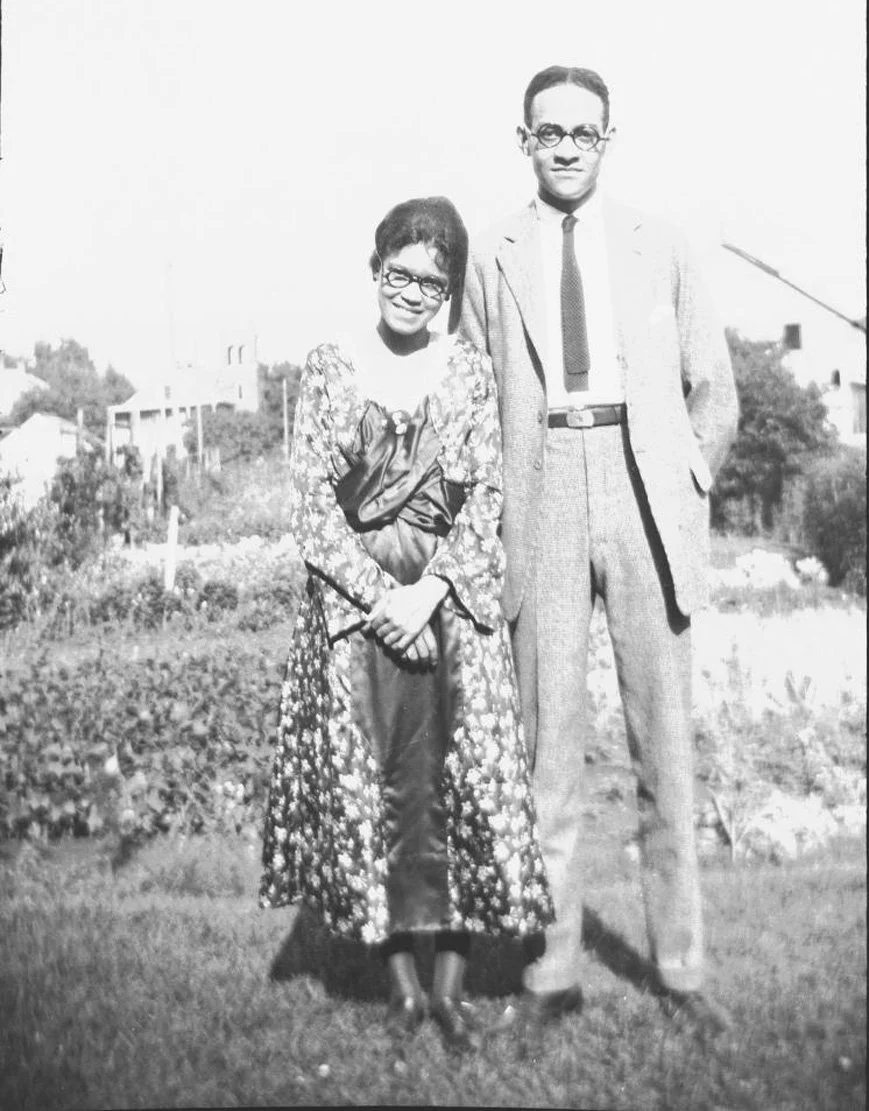

In 1923, Sadie Tanner Mossell married Raymond Pace Alexander, who had just graduated from Harvard Law School. The wedding took place in the home of Bishop and Mrs. Tanner, 2908 W. Diamond Street.

Upon graduating from The University of Pennsylvania Law School in 1927, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander became the first African American woman to pass the Pennsylvania bar exam and practice law in the Commonwealth. Sadie T. M. Alexander joined in partnership with the Alexander Law Firm, located at 1900 Chestnut Street and later 40 South 19th Street, an impactful provider of civil rights and civil liberties to all people, particularly those denied constitutional rights because of race, gender, and economic status. In addition to the firm’s founder, Raymond Pace Alexander, there were five male attorneys, each a graduate of a distinguished law school and admitted by the Pennsylvania Bar Association to practice law in the Commonwealth.

The Alexander Law Firm was the first law firm in Philadelphia and the wider Commonwealth of Pennsylvania dedicated to civil rights litigation. I stress the Alexander Law Firm's addresses because they reflect the first presence of Black businesses and property ownership in the all-white, highly commercial Center City of Philadelphia. These properties demonstrated Raymond Pace Alexander’s commitment and that of the firm to providing outstanding legal redress to their clients in a setting that showed respect and a sanctuary for those seeking help.

As a teenager, I remember the legions of clients who could not leave their workplace during the day and come to Center City were welcomed to our home in North Philadelphia to discuss legal issues with either Sadie T. M. Alexander or Raymond Pace Alexander.

In the late 1930s, the Alexander Firm took two Chester County school districts in Berwyn, Pennsylvania, to court after they tried to establish racially segregated school systems. In this case, Raymond Pace Alexander's victory marked an end to de jure segregation in Pennsylvania’s public schools. The Alexander Law Firm’s clients represented a large, economically, and racially diverse cross-section of Philadelphia, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and the nation.

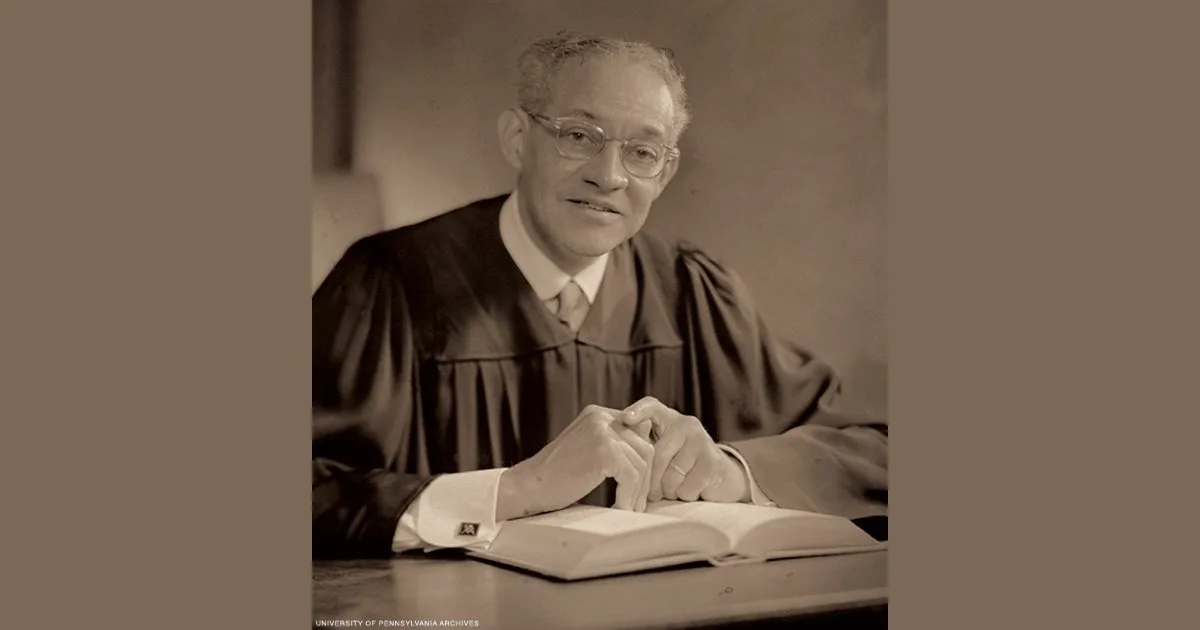

Harvard Law School Professor Kenneth W. Mack, in his book Representing the Race: The Creation of the Civil Rights Lawyer, described Raymond Pace Alexander “as one of the best trial lawyers in Philadelphia, regardless of race.” These legal skills and acumen were more than evident in the Trenton Six Case of 1948, where Alexander won a case that cleared the two defendants he represented, all of whom were Black, falsely accused of killing a white shopkeeper.

Sadie Alexander’s negotiation skills and growing fame positioned her as the recipient of “the most desirable client for a law firm, the Black Church.” She was designated the lawyer for the AME Church, which W. E. B. Du Bois understood the AME Church as “the greatest social institution of American Negroes,” and a bastion of male dominance.

In December 1958, Raymond Pace Alexander received a telephone call from the term limited Governor of Pennsylvania, George Leader. I took the call from the Governor; my mother was abroad in India on a speaking engagement. In a “midnight decision,” Governor Leader appointed Mr. Alexander to the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia, the first African American to hold this position. The weeks and months following the announcement of this appointment were fraught with acrimony, charges of racism, and death threats. The Alexander Law Firm was dissolved in 1959 when Raymond Pace Alexander assumed his judicial appointment.

During his 15-year career with the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas, Judge Alexander sought to sustain human rights and justice for all defendants in his decisions. Judge Alexander died in his judicial chambers at age 76 from a cerebral hemorrhage on November 25, 1974.

Sadie T. M. Alexander continued her law practice in new quarters near City Hall, Philadelphia's political and judicial epic center. Her thriving law practice of Black, White, and Brown clients emphasized family law, protecting and safeguarding the rights of women, children, and older people most subjected to inequities. Mrs. Alexander, grounded in the law and economics, addressed in her practice and wrote of the need for equity for all, particularly women, who suffered from the indignity of low wages, inadequate child care and health care, and the devaluation of their constitutional rights.

Sadie T. M. Alexander remained civically and politically engaged. She maintained her board membership on the Commission on Human Relations, which she chaired from 1962 - 1968, dedicated to human rights. Sadie Alexander was one of two Pennsylvania founders of the American Civil Rights Union (ACLU). She spoke worldwide on the “sting of racial prejudice,”writing and publishing position papers to end this pernicious practice.

On November 1, 1989, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander died after a long illness of Alzheimer's and Parkinson’s disease. She was 91 years old. In 2007, the Law School of the University of Pennsylvania established a Chair in Civil Rights named in honor of Raymond Pace Alexander and Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander. Dean Michael A. Fitts of the Law School described the two-decade quest as a “landmarked decision.”

ON MY LIFE’S WORK:

My personal interest in the evolution of Black communities in the United States began as a doctoral candidate at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education in 1974. My doctoral dissertation was an ethnographic/ethnohistoric study of Frankford, a 19th-century African American community in a predominantly white ethnic enclave in Northeast Philadelphia. The grants I obtained allowed me to hire graduate students to train Philadelphia Public School junior high school students, Black, Brown, and White, as “junior historians,” steeped in the techniques and traditions of oral history and successfully interview the elders of this community.

The Frankford Project was PennGSE's first collaboration with Philadelphia’s public schools. Before Frankford, the GSE worked only with suburban public schools. My doctoral committee included the then Dean of GSE, the anthropologist and linguist Dr. Dell Hymes, the Folklorist Dr. Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, the anthropologist Dr. Peggy Reeves Sanday, and the educator Dr. Morton Botel. I was awarded my Doctorate in 1981.

In a private conversation some time ago with the then-Dean John L. Jackson, Jr., of The Annenberg School of Communications and now Provost of the University of Pennsylvania, he told me that my dissertation influenced PennGSE’s decision to broaden its curricula, including anthropological research. I believe that Dr. Christopher Rogers, co-founder and current director of the Friends of the Tanner House, is a recent graduate of this program.

Today, the United States is in a crisis. The moral fabric that binds us together has shattered— perhaps it never was there. We have lost our compass in a cacophony of lies and untruths, resulting in the Race Replacement Theory. Books by noted Black writers and LGBTQIA authors are banned. Affirmative Action is dead. In many states, women’s gynecological concerns are now determined not by medical professionals but by legislators and the judicial system. Historic African American communities are facing demolition from voracious developers who see gold in the Black soil.

The Friends of the Tanner House sits on the precipice of a momentous historic moment. They have valiantly awakened our knowledge of the material culture of North Philadelphia in the restoration of the home of the Tanner Family. However, the Tanners and their progeny were not an anomaly in 19th and 20th century North Philadelphia. Many more Black families and individuals whose history needs recognition and rigorous study contributed to a warm, welcoming, and cohesive community of doctors, nurses, teachers, secretaries, administrators, law enforcement officials, domestics, judges, municipal employees, laborers, and Public Assistance recipients.

What happened to North Philadelphia over time? Social scientists, municipalities, public policy analysts, and demographers, among others, must answer that question.

The scholarship of Harvard sociologist William Julius Wilson is central to our understanding of this vexing phenomenon, which is visible throughout the United States. I would use Wilson’s analytical demographic and economic template to undergird an ethnographic/ethnohistoric study of North Philadelphia. In addition, I would garner the oral history of residents and the descendants of residents now deceased to provide valuable oral history. Of course, much more work needs to take place, i.e., the history of North Philadelphia, demographics over time, census data, housing stock analysis, transportation routes, public schools, libraries, religious institutions, medical facilities, politics, etc. I hope that this research will occur.

THE PURSUIT OF THE WORK AHEAD:

African American urban communities, rich in history, are located throughout the United States and are worthy of studying and documenting to further our understanding of Black Americans' cultural history and evolution over time. However, they most often do not attract the attention of academics and municipal leaders because they do not appear necessary.

Herewith are the names of seven historic Black enclaves whose futures are threatened by the influx of gentrification and rapacious developers:

North Philadelphia,

Harlem’s legendary Sugar Hill community,

Chicago's Bronzeville,

Detroit's Arden/Boston District,

Boston's Roxbury,

The Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina,

Washington, D.C.'s Shaw Community.

The project conceived by The Friends of The Tanner House has skillfully unearthed the evolution of a potent, stable, Black community whose residents once comprised doctors, lawyers, clergy, teachers, school administrators, domestics, industry workers, and Public Assistance recipients. What you have done so far in acknowledging and protecting the Tanner House's material culture is profound and transformative.

You have highlighted the historic riches within the so-called Black Ghetto of North Philadelphia and in Black communities nationwide. Within the material culture of these historic Black communities, we find Black residents' vibrant strength, resilience, and copious intellectual pursuits, often not comprehended by mainstream culture as valuable.

I view the Friends of the Tanner House as a beacon to further the ancestors' work. They are transforming the prevalent misunderstanding of the Black community as pathological wastelands and its residents as vacuous and void of intellect and creativity.

“I was born in North Philadelphia; I know its significance. We must ensure that its history, our history, is preserved. What would it mean for schoolchildren to see that they lived in such a historic community and were its future for survival?”

The Friends of the Tanner House have widened the social science threshold and moved the ancestors' scholarship into the 21st Century. In so doing, they pay homage to the prophetic words of W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in his seminal treatise, The Souls of Black Folk (1903): " ... the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.” North Philadelphia is a pivotal community in understanding the dissolution of a strong, economically pluralistic urban Black community over time. I leave the analysis of this heart-wrenching phenomenon to the Friends of the Tanner House to research the answers. May I suggest that the demographic/economic scholarship of Harvard University sociologist Dr. William Julius Wilson serve as a helpful model for answering these questions?

—Dr. Rae Alexander-Minter, July 23, 2024.

APPENDIX: ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

The following is a short list of books the ancestors and their disciples wrote. Each book addresses the issues I have delineated in this position paper. Please find these treasures and engage with them.

Horace R. Clayton, One Caste Class & Race, 1948

Kenneth B. Clark, Dark Ghetto: Dilemmas of Social Power, 1965

Allison Davis, Burleigh B. Gardner and Mary R. Gardner, Social Anthropological Study of Caste and Class, 1941;

Thulani Davis, The Emancipation Circuit: Black Activism Forging a Culture of Freedom, 2022;

Matthew Desmond, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, 2016.

St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Clayton, Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City, 1945

W. E. B. Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study, 1899

Mitchell Duneier, Ghetto: The Invention of a Place, The History of An Idea, 2016.

Sadie Mossell, The Standard of Living Among One Hundred Negro Migrant Families in Philadelphia, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1921

Hortense Powdermaker, After Freedom: The Portrait of a Community in the Deep South, 1939;

William Julius Wilson, The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy, 1987;